Tibet has often been cited as the true location of James Hilton’s mythical fantasy land of Shangri-La. Between the mountaintop prayer flags, monasteries of chanting monks and wafting insense, you can really appreciate the likeness – although perhaps not so much now with the Chinese troops on the streets and jarring horns from each passing motorbike and car.

However, as we crossed into Nepal at the border town of Zhangmu, there seemed to be more of a resemblance to the modern day imitation Shangri-La at Glastonbury Festival than that of 30’s literature. Darkened alleyways with flickering florescent lights; narrow streets lined with mysterious shops bearing indecipherable Chinese script; sanitised quarantine zones for immigrants with quasi-english directions; and salubrious red-lit doorways with ‘hostesses’ awaiting their next customer. Ok, Glastonbury doesn’t have the last bit, but its sensory overload night venue is a fair representation of the contrast we saw in the last night we spent in Tibet.

We’re now in Kathmandu, Nepal, collecting our thoughts and future plans before embarking on the next step of the adventure. We arrived on Sunday after a journey through a landscape that felt more like Costa Rica than our expectations of a landlocked plateau.

The border was both classic and bureaucratic. A single lane bridge over a river cut through a deep gorge, with soldiers from each side arranged next to the line of control – the stuff of Cold War movies (or the opening sequence of Die Another Day for the younger generation). Then a laborious hour-long process of form filling, stamping, correcting, re-stamping and finally getting the signature of the chief immigration officer, who has to personally sign each visa. By hand. Not that the visa was actually needed to enter the country – the visa office was just a door on the street that we could well have just wandered past and into town if we didn’t have a guide with us!

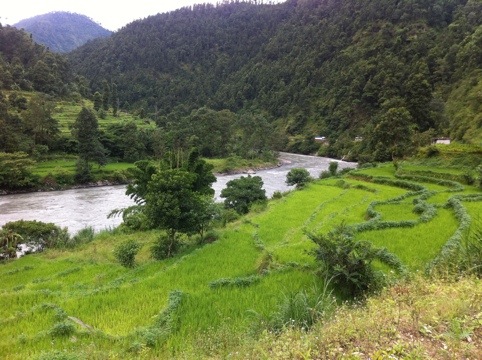

The Costa Rican element of the journey came from the glorious green forest cut by a wide river, around which our dusty and landslide-evident road wound and precariously leapt. Luscious, balmy and humid – none of which I’d have previously thought would fit Nepal. Oh, and cramped, sweaty and bumpy on the bus, which fitted the bill more!

So we bade our farewells to The Rooftop of the World, and to the great friends we’d made on the trip from Beijing. We’re hoping to catch up with some folks in Delhi in a few weeks time, and others hopefully back in London – or elsewhere in the world. It’s strange to think back now to three weeks ago, indulging in Peking Duck on the first night, and the experiences we’ve had since then – seeing hundreds of people doing salsa/chinese crossover dancing on the streets of Beijing at night; shopping in The Gates Of Hell (massive supermarket, I’ll explain another time); crazy food – and being ripped off – at the night market; friendly shared gestures and photos with Buddhist Nuns; and the sight of Everest at last after the longest bumpy road imaginable!

Kathmandu feels so much more like India than China, with brightly coloured hand-painted adverts covering shop shutters, the continual screech of car horns (often musical), and the fabulous wafting smell of curry. It’s a lot more frantic and noisy than I’d imagined – probably closer to my vision of Bangkok than a centre for trekking. Each narrow street of the Thamel district is teeming with honking motorbikes and rickshaws jostling for space among the pedestrians, and it’s easy to get a headache after just a few minutes.

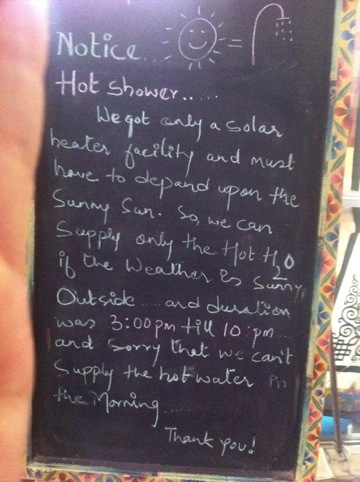

We spent a final night basking in the delights of a hotel room (with windows on three sides, no less!) before downgrading yesterday to a twin room at a hostel (en suite) for 1/10th the price. Cell-like – yes, in need of a good clean – definitely, but cheap as chips at £3 each per night. And with wifi and a rooftop view over the valley – bargain!

Yesterday we accidentally* wandered into the middle of one of Nepal’s biggest festivals, which was bemusing. Appropriately we arrived just as the various ambassadors of the world were driving up to palace in the main square here, and we slotted into the peculiarly prominent tourist area, waved past lines of riot police tasked it seems with holding the locals back from seeing their own festival. In short (this post is way too long already, but I’ve got to finish this now!), six year old living goddess, her feet can’t touch the ground, she gets out once a year – on this day – and rides a chariot (people, not horse-drawn) around the old town after blessing the president for another year of rule (it used to be the king but that stopped after he massacred his whole family ten years ago). Oh, and a dancing elephant (more people, not real animals), and man with a huge red hat. For three hours in the hot sunshine. It was certainly an experience! Then a final dinner with the remaining Gap Tour folks who had stayed an extra day.

Today we procrastinated and sat out on the roof garden of our hostel, admiring the view while Laura beautified her scrapbook and I watched a huge raincloud wash in over the valley. It’s lovely and (relatively) quiet here compared to the bustle of the Thamil area 5 minutes walk away – the distant car horns sounding more like quietly bleating sheep, fitting nicely with the surrounding vista of green hills and dreams of mountain passes and trekking adventures.

Tomorrow we need to actually plan our trek and start the journey onwards – but for tonight, it’s a cosy meal somewhere easy and then curling up with a book, possibly by candlelight if the one of the city’s regular power cuts sweeps in before we sleep.

Simon

* Apparently we were told about it by some friends from the trip, but I’m denying all knowledge.