Jaisalmer (pronounced like Haselmere) is known as the golden city thanks to its honey coloured sandstone streets that emerge from the dust and heat of the desert. The city lies on the edge of the Thar desert, a parched land in the far northwest of India 100km from the border with Pakistan. We’re closer to Karachi than Delhi, and the furthest west we’ll be during the Asian part of our travels.

I don’t think any description of a desert land is complete without some mention of the temperature and an unscientific reference to egg cooking time. So for the record: it’s very hot and dry here, albeit only touching 37C on the forecast, and the midday sun is scorching – certainly hot enough to fry an egg on a car bonnet in 30 seconds or so – although with all the dust I’m not sure we’d eat the egg if we did cook it! Actually, it’s hot enough that for the first time we’ve had to seek shelter during the middle of the day and explore during the cooler hours.

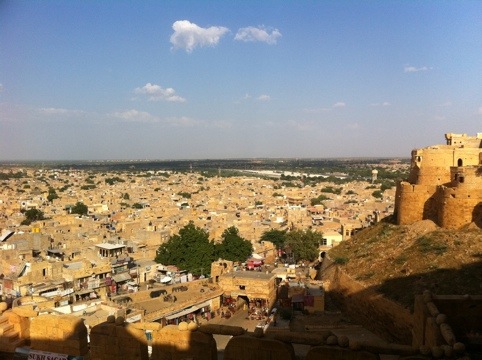

The city holds one of the world’s oldest living forts, with 2000 people still inhabiting the houses of the hilltop fort at its centre. While not as vast and dominating as that at Jodhpur, the fort itself is nonetheless impressive – a golden spectacle rising 100m from the town below, with the usual twists and turns on its entry road to prevent invaders from building up enough speed to batter down the defences. It was never successfully taken by force, with the three times it was overcome only after sieges lasting many months forcing those inside to admit defeat and ceremonially surrender in a desperate act – the women by throwing themselves on a ritual fire dressed in all their finery to the beat of a drum, and the men in one final fatal battle charge knowing they were outnumbered and hoping to take as many of the enemy with them as they could.

Despite its impressive past, this is now a citadel in crisis – the modern day development of having water on tap has outstripped improvements to the fort’s old sewer system, and as a consequence a large proportion of the water used in the fort seeps into the foundations beneath, causing collapses and in a few recent occasions catastrophe. Tourism has a large part to blame, and the advice is to stay outside the fort (as we did), or only use one of the older, eco guesthouses within.

The fort plays host to a number of temples, including an ornate Jain complex from the 16th century, as well as a palace. All are decorated in fantastically detailed stone panels, carved with such precision and deftness that you’d think it was wood. Set against the dazzling blue sky, these golden monuments really look stunning, and all the more so for remaining so detailed after hundreds of years facing off to the abrasive desert winds. In addition to human inhabitants, the buildings of the fort also accommodate an impressive range of bats – almost every indoor corridor had its ceiling dotted with them, sleeping and occasionally stretching and yawning just above our heads.

Earlier today we went down to the lake which used to be the town’s only water source. We hired a pedallo and were able to admire the reflections of town and fort upon the water – and at the same time reflect for ourselves what an importance this site must have been before the days of taps and pumps, when the womenfolk of the fort would walk the two kilometres downhill to collect water each day, and when various architectural features of the palaces were first designed to retain every last drop for recycling such a precious resource. It’s just such a pity that today’s throwaway world has seen this quite literally undermined through careless and thoughtless wastage, or to look at it another way, through unbalanced, short-termist development – improvement in water in without matched improvement in the sewerage system to get it out.

The highlight of our time in Jaisalmer was undoubtedly a camel trek we took into the desert, over two days with a night under the stars in between. We set off early one morning by jeep to our starting point an hour’s drive out of town, where we met our camels and guides. We were fortunate to be just four in total, having been joined by a German and a Cuban girl from our hotel, who made up for in enthusiasm what she lacked in English!

Camels (or in our case, single-humped dromedaries) are strange animals, a true dinosaur of the desert which seem to have few present day equals. To look at them and hear them groaning, chewing away at the bushes, and scratching on branches to destruction, you could well think you were watching a scene from Jurassic Park. They stand at easily over two metres high, with impressively long giraffe-like necks that let them crane to reach the juiciest greenery from up on high. And then there’s the legs which are double-jointed and fold concertina-like to let the animal kneel and sit. It’s a strange multi-stage manoeuvre to go from on the ground to up in the air, but it works, and we fortunately managed to stay on! It brought back memories of our brief jaunt on camels in the Tunisian desert – we missed you Steve!

As we started out in our rolling rhythm, there was one surprise about the desert – it was a lot greener than we’d imagined! No, we hadn’t been conned (we did check our GPS to be sure!), but we’d instead visited at one of the few times when the desert is briefly green, after the rains of the monsoon. It will now not rain again here until next July, when another 30cm or so will fall. On a bed of yellow sand, there was a matting of slowly withering grass, in shades of light green and yellow, interspaced with darker green shrubbery – a low stringy dark green plant with small leaves that clung to the ground that our camels seemed to love, and occasional bushes one or two metres high, with glossy bright green leaves. The camels were blighted by flies and in an effort to rid themselves of the irritation, they would crash into these larger bushes, creating a fantastic ripping and tearing sound as the branches and leaves were torn off, and we as riders clung on. However, as Laura found to her peril, the most dangerous obstacles were the spiney, prickly thorn trees that were apparently perfect to scratch that camel itch that apparently no other bush could reach. Unaware of the plight of their human rider, the camels occasionally plunged sidewards into one of these, at one point scratching Laura’s hand and arm

in the process. Fortunately we’re both generally still intact from the experience!

We stopped at a village along the way, where bizarrely Laura got her nails painted in what must be the strangest cultural exchange of the trip so far! After being shown around the simple thatched hut the family lived in and taking the customary photos of the kids posing in our sunglases, the woman pulled out a container of sparkling red nail varnish, and kindly, if not that accurately, decorated Laura’s fingernails. There was a slight moment of horror when she apparently reached to also paint Laura’s nose the same way, but we were relieved to find she just left a small bindi-like spot of red on the end of her nose instead. Even as I write this, I can see Laura’s nails sparkling as a testament to our cultural interaction – still there despite the very best efforts of nail varnish remover last night!

Food in the desert was cooked by our guides over an open fire, delicious and fresh. Each meal was accompanied by handmade (in one case by Laura) chapattis, along with a tasty veg curry and green – but apparently ripe – oranges.

The creatures of the desert were interesting not for what we saw of

them – thankfully very little – but more for the evidence of their presence and survival amid the hostile sands. Holes of varying sizes dotted the sand, some just a few millimetres across, some a couple of centimetres, and others more a warren of tunnels for desert foxes or rats. We didn’t really want to dwell on the creatures of the smaller holes – beatles, certainly (and we saw some rolling dung back with them), but spiders? Scorpions? Fortunately we didn’t need to find out!

As you can imagine, in this context, it was with slight trepidation that we lay down to sleep after a beautiful desert sunset. Our guides had made wonderful beds of clean white sheets and blankets right on the sand, and Laura and I had the privilege of a whole dune to ourselves, with only the starry night sky above and nobody else in sight. The full moon slightly undermined our ability to see the stars but it was a brilliantly beautiful way to sleep, and I was relieved in the morning to find the only close visitors we’d had were beatles, whose tracks decorated all the surrounding sand. Slightly further away was the small wavey track of a small snake that had been past, but we were assured there was nothing hazardous to us.

I never cease to be amazed by dawn, and sunrise in the desert did not disappoint. The gift of day is carefully packaged, and witnessing nature unwrap it is a methodical but wonderfully gradual process.

Before it all begins, there’s a change in the music – a gentle dimming of the night humming of crickets, and an almost imperceptibly slow crescendo of tweets and chirps and caw-caw bird calls, which will build into a fanfare. Then the unwrapping begins. The first layers offer the prize of contrast and shape – the ability to distinguish between the curves of the dune we’re lying on and those of the next; the texture of the sand and its many animal prints from the night; and the first hints of silhouetted trees against the lightening sky.

Then comes colour. The dull colour wash of the moonlight is repainted with ever more vivid highlights – the sky taking on streaks of pink and light blue, giving way to oranges and turquoise, while the sand around us becomes ever more golden and the shrubbery take on their daytime palette of glossy greens and yellows, over rough browns and blacks. It’s almost like discovering sight all over again – as you look around you’re convinced that sunrise must now follow as all the colours of the day have arrived, only for another to emerge from its slumber – a deeper hue of green in the trees, a stronger pink in the sky, an even brighter white in the sheets of our beds.

Finally, the sun emerges, bringing with it incredible blinding brightness, and with that, shadows and the absolutes of black and white – the crisp outline of the distant trees against the glowing sky, and the full shape of the mounds of sand around us as the shadows work their magic and depth comes into play.

Less than a minute later the unwrapping is complete and the day is on full show, the whole glowing sun providing a reminder that we’re in the desert with its lasting final sensation – that of heat, and the need for us to pack up our beds for the night and find shelter in the cool shade of the trees before continuing our journey for the day.

Simon