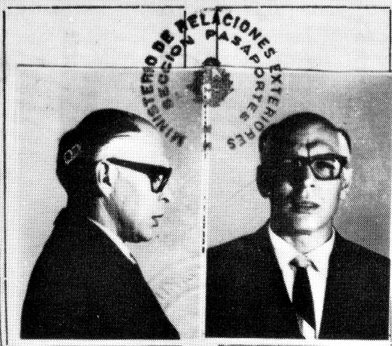

Photos of the disappeared hang over a street in Cordoba

When in Buenos Aires, and again in

Cordoba, we visited sites used during Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’. In almost every country we’ve been to, we’ve found unspeakable horrors visited on the population in the recent past – and this was no exception.

In 1976, a bloodless coup once again put the military in charge of Argentina. At the time, there were a number of prominent left wing opposition groups, filling the full spectrum of approaches from political party to violent guerrilla terrorists. With popular (albeit not democratic) support from the press and a population whipped up into a fear of the extremist leftist terrorists, the military set about destroying these groups, in a ‘National Reorganisation Process’, known less euphemistically as the ‘Dirty War’.

Between 1976 and the end of the military’s reign after the Falklands war in 1983, it is believed that as many as 30,000 people were ‘disappeared’ – kidnapped, tortured, and in almost every case, killed. What is perhaps most chilling is that this happened in plain sight, in a modern and civilised society with a functioning press – and with support from other western nations, particularly the US as part of its global fight against the threat of Communism.

In other places we’ve visited, it has seemed possible to attribute the horrendous actions of those in power down to a form of madness or at least a lack of awareness, and that lack of logic made it easier to digest and understand. Mao had his swirling, vindictive personality cult, and held the view that progress was only possible through violent revolution. The Khmer Rouge in Cambodia swept in with absolute blood-filled insanity, tearing society apart at the seams to achieve the same goals as Mao but in a matter of days – and given the pace at which it was imposed, it’s no wonder that there was little organised opposition. And on the other side of the political spectrum, through the ‘Vietnam War’, the USA unleashed hell on the people of not only Vietnam, but also Cambodia and Laos – with a hell in chemical form to follow for decades later.

I think what hit me hardest in Argentina was how the actions of the military were so clearly calculated, part of a logical, forceful political strategy, and it was conducted in full view of the public – or at least as much visibility as for example the German public had under the Nazis. Did we learn nothing?

The Naval Mechanic School in Buenos Aires where some of the worst atrocities occurred

People who were considered opponents of the regime were kidnapped, sometimes in the street in broad daylight, and then taken to interrogation centres, where information was extracted under torture. Once they had served their useful purpose, they were generally then killed – through military ‘death flights’, where the unconscious victims were dropped into the sea from a plane, having been told they were being transferred to a prison and to be given a ‘vitamin injection’ which was in fact a sedative. Even in this respect there was a stark contrast in organisation to what we’d seen in Asia: the Khmer Rouge had avoided using even bullets to kill their victims due to the cost; dropping people from planes is an expensive way to massacre a population.

A basement at the interrogation centre in the heart of Cordoba

Amid this utter horror of systematic torture and murder, you then have this bizarre notion of ethics – for example, a priest blessed the plane from which people were then dropped to their death. I think this really shows how some of those involved really did think they were doing

the right thing in order to fight the threat of the extreme left, or at least found cover in the support of the church. “We are not monsters” is the phrase apparently used at the time.

Another situation where these uncertain moral lines show is when pregnant women were among the disappeared. The interrogation centres had special areas to care for such women until they gave birth; our guide explained to us that the interrogators felt that the baby should not be punished for the actions of its parents and so should be allowed to live. However, they also felt that the child should not be given back to the remaining family who had been associated with such leftist views, and so the child was secretly adopted by a new family who supported the regime, many of whom were in positions of power. Argentina now has a movement ‘The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo’, representing those who lost their children but still have grandchildren out there somewhere. They encourage those who were born during this period to verify their heritage; it is believed that some 500 children were appropriated by the state and given to new parents – to date 105 have been identified. One can only imagine the anguish that those now-adults go through to discover their true parents were killed, and that their adopted parents with whom they have grown up were likely complicit in what happened.

And there’s so much more; the Trade Unionists in factories working for well known multinationals like Ford who were disappeared en-mass and held in camps in the factory grounds; the secret island owned by the Catholic Church to which prisoners were relocated when the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights came to inspect the interrogation camps on the mainland; the two different estate agents run by the navy to sell off the appropriated houses from those they had killed. This was clearly a systematic and widespread process for purging those who disagreed with the regime, with the support of the church.

A police mural on the wall in Cordoba

All this happened at a time when through Operation Condor the USA was providing support to South American nations fighting communism. Through the ‘School of the Americas’, many of the Argentine naval officers involved in these atrocities were taught techniques of interrogation and torture, and how best to tackle the threat of the left. Given this, it is not surprising that there is so little trust of US foreign policy interventions now in South America.

I got the sense that this whole period is something Argentina is still very much trying to come to terms with – to find a way to justify what had been allowed to happen and why, and to find justice for so many victims. Few records were kept about those who were taken, and those involved at every level are still refusing to talk about it, so there is a huge gap in knowledge about what happened. But there is one thing our guide said again and again that really stuck with me : ‘nunca más’, ‘never again’. As she reiterated, everyone, everywhere has the right to a fair trial and transparent justice, even if they are being accused of mass murder or terrorism. I think we all would say the horrors of Nazi Germany or of the Dirty War should never be allowed to be repeated, but it’s a slippery slope. She drew parallels to Guantanamo bay, extraordinary rendition and the various processes going on right now around the world where people are being held, punished and sometimes killed without trial. In that context, one really has to ask oneself when we will ever truly mean those words ‘nunca más’.

Simon

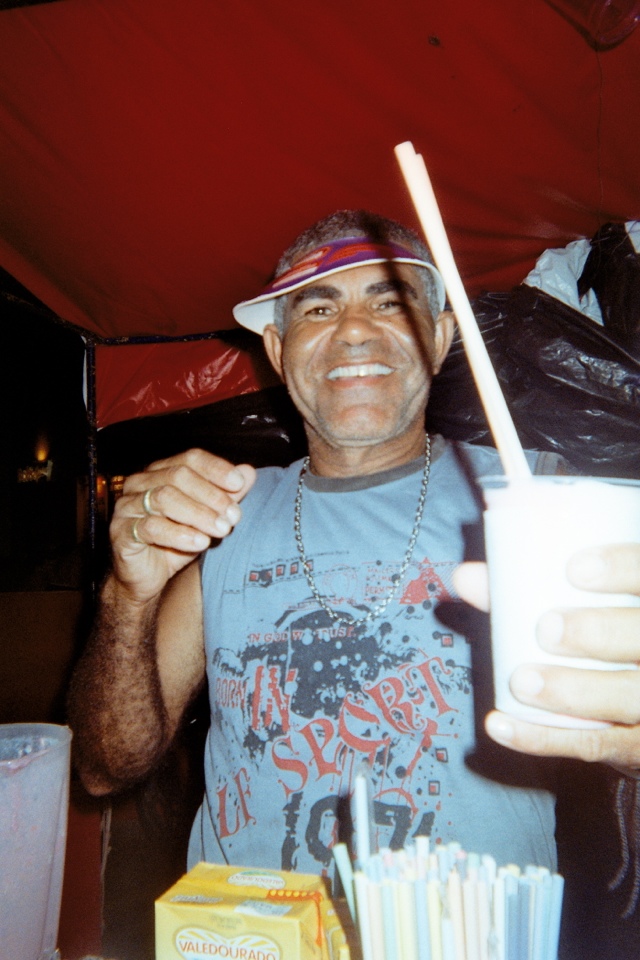

Photos of some of the disappeared, Cordoba

A broken doorway, Cordoba