Fantastic architecture in Havana

Cuba is a warm blur of sensation and emotion. It is colour and heat and music, and altogether different to everywhere else we’ve been. For me, it also comes with a feeling of satisfaction: a wish for many years finally delivered – ‘we are here in Cuba‘, we keep saying to ourselves. But it also brings a sense of conclusion: after nearly 11 months of travels, this is our final country, a two-week holiday at the end of a trip of dreams – and some surprising realities.

I’m writing this sitting in a wooden rocking chair on our porch in the early evening sunshine, looking out in the distance at a panorama of palm trees and tropical forest covering a limestone rock formation – and in the foreground, the more comical quiet street where a horse has broken free of its tether and is making its way through all the gardens for dinner. Somewhat symbolic of this friendly, sharing culture, nobody seems to mind – including the house owners sitting out in their respective chairs. And as if this picture of idyllic beauty needed liquid accompaniment, our landlady has just brought out ice-cold mojitos. Oh yes: Welcome to Cuba!

When we were driving out of Havana the other day, we passed one of the slogan billboards that are everywhere here, and it struck a chord. “Sin cultura, la libertad no es posible – Fidel”, “Without culture, liberty is not possible” (and that’s a direct quotation, it’s first name terms with him here). It seems to capture the feel of the place: yes, this is one of the last remaining communist states; yes, there is effectively rationing, close state control and in places brutalist soviet concrete architecture – but yes, there is also vibrant, colourful and enthusiastic life on the streets: real culture. Almost everyone we’ve met has been overwhelmingly friendly and welcoming – and not demanding of money as we’ve found elsewhere. (OK, so Havana is a bit of an exception, but its certainly nowhere near as bad as other places we’ve been). The live music and dancing is brilliant, and I think its fair to say we’re captivated by the whole thing.

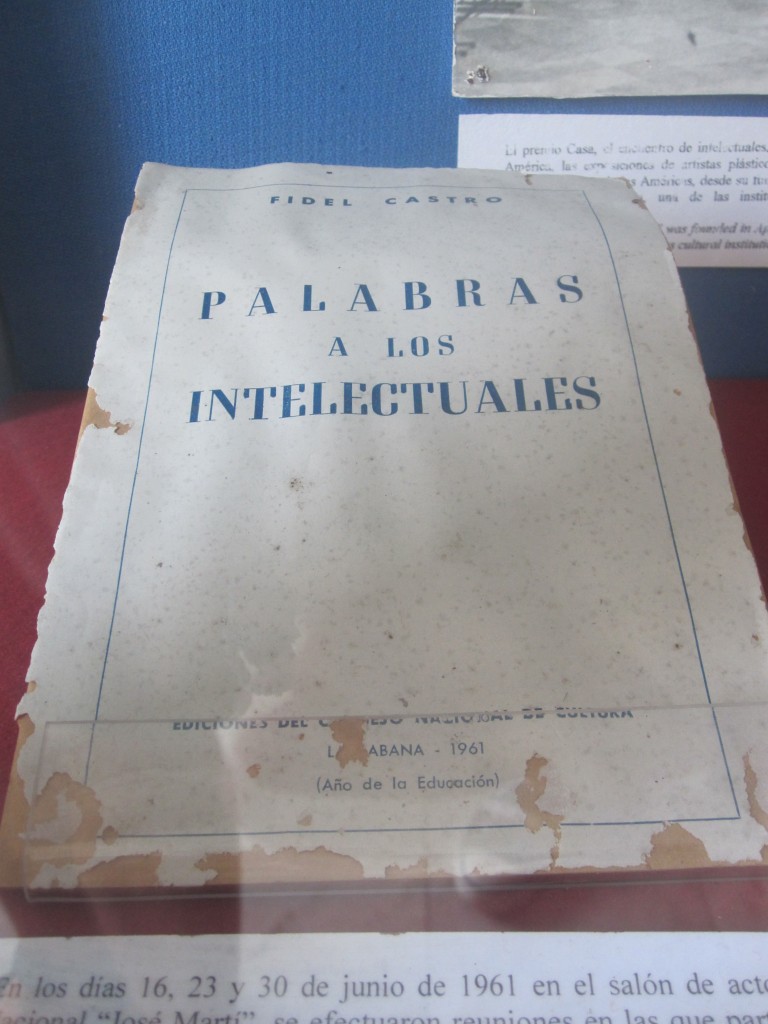

Of course, as the millions of exiles in Miami would no doubt point out, there is another side to all this – one that’s essentially invisible to us as wealthy foreigners peeking in from the outside. I think that’s why I really like that slogan, for it can be so easily turned around: surely “Without liberty, culture is not possible” too? One of Fidel’s key rules about cultural expression was apparently “Within the revolution, anything; against the revolution, nothing”. It’s not hard to see how that means public political dissent is simply not possible – but that certainly isn’t the slightest bit visible in the positive energy we’ve found on the streets. This is not China, and certainly not Tibet.

Facade supported by scaffolding, which has been up for so long its become a jungle!

Iconic images appear everywhere you go like some photographer’s picturesque fantasy land: I keep having to ask myself ‘is this real?’. It is! The anecdotes just write themselves. That includes the dusty cowboy on horseback who’s just trotted past, complete with picture-perfect spurs on his boots; gleaming vintage American cars, curvaceous, huge and colourful; and the mildewed decaying architecture of Old Havana and Trinidad where you can witness at first hand the physical impact of 50 years without imported building materials and state priorities other than a glossy facade.

Our Cuba experience really began when we were queueing to board our flight in transit in Caracas. Yes, there was the ludicrous beaurocracy of needing to buy a tourist visa in local currency before boarding the flight (which we didn’t have, being in transit). Much more significant were our fellow passengers – or rather their hand baggage. It felt a bit like we were in Dixons during the January sales. Everyone seemed to be carrying boxes of electrical items, flat screen TVs, rice cookers and power drills, importing what the blockade has essentially stopped. For the first time in a while, we felt we should have been carrying more with us!

It’s not hard to see the problems Cuba has faced in its near-total isolation since the fall of the Berlin Wall. There’s a general principle here of make-do-and-mend that means everywhere except the fanciest of tourist hotels has a sense of decay and faded glory about it; new buildings (and actually, new machinery) are generally absent. Alongside those iconic classic cars, what little traffic there is comprises rusting old red tractors, motorcycles with side cars, VW Beatles, and horses and carts actually being used as transport and not just for quaint tourist trips. The exception amid all this is the odd new shiny small car, which look totally out of place. Government workers perhaps? Who knows. For most, the conventional intercity bus is a case of standing in a big old belching dumper truck, which if you’re lucky has had some metal crudely welded to give the passengers a roof and possibly some seats.

It’s not all quite so drastic though. Cubans have essentially been forced to save the few resources they have for what really matters – and the state has decided that is education and healthcare. The literacy rate of 99.8% rivals any developed country – it’s no wonder we’ve found the most local English speakers here, giving travelling around a distinctly ‘easy’ feel to it. The country also has 75,000 doctors – compare that with 50,000 for all of Africa. After the earthquake in nearby Haiti, it was Cuban medics who were some of the first on the scene, and were still there recently as some of the only aid workers to help tackle a cholera epidemic – 40% were treated by Cubans. According to our guidebook, 1.8 million people outside the country had their sight restored by Cuban aid worker doctors in the five years up to 2009. Take these indicators of welfare hand-in-hand with low resource consumption (even if just by necessity) and a society that isn’t entirely materialistic, and you can see why a 2006 WWF report named Cuba as the only country in the world actually living sustainably. Quite a different perspective to the communist demon projected by some.

Viva la revolución

As I write this, the man living in a pink house opposite has just nailed up a handwritten cardboard sign in his garden. It says “Viva la revolución”. Although the cynic in me says he’s just some over-zealous official seeking party credit, you can’t help but get the sense that for many, there really is emotion behind the slogans; despite the visible problems, things are still working working and Cuba continues to set an example – even if not a model – of a different world. It will be interesting to see how long it continues once the Castro dynasty have themselves reached their end.

Simon

-

-

Chinatown in Havana

-

-

The Capilolio building – no, this is not Washington DC

-

-

The Capilolio building

-

-

A typical Old Havana street

-

-

Facade supported by scaffolding, which has been up for so long its become a jungle!

-

-

Revolutionary slogan next to a rusting yard

-

-

Abandoned rubble everywhere

-

-

Crumbling Old Havana

-

-

Fantastic architecture in Havana

-

-

A beautiful church built to appease relations with Russia – and a Coco taxi in the foreground

-

-

Che and some classic cars

-

-

Cool sculpture

-

-

The monument in the Plaza de la revolucion. The black dots are hundreds of circling eagles…

-

-

This is the plaza where the big political rallies are held

-

-

Viva la revolución