We went out for a posh dinner in Havana the other night to mark the end of the trip, and after much debate concluded that Cuba is the best country we’ve been to. It has it all: warm weather, decent homely food, tropical jungle, beautiful beaches with clear water and white sand, fantastic architecture, fascinating politics – and people so friendly you want to hug them all. A perfect way to finish – only of course it means that now we don’t want to leave.

All in all, it still remains a bit of a puzzle. There are two currencies, which effectively segregate things into tourist (CUC) and local (MN), and although we got our hands on a fair bit of local money for great 5p ice cream and fold-up pizzas, there was a lot of that local way of doing things we just couldn’t reach. Obviously things are much worse for the locals, for whom a 20 CUC ($20 USD) monthly wage is not unusual; when you consider even a cheap on-the-street fold up pizza is 10MN – or 0.40 CUC, life isn’t easy. As I’ve said before, from our capitalist perspective we find it hard to understand why people go through all the trouble to train as doctors, when they get much less income than those who work in tourism – and after a lot less training. Many of the Casa Particular owners we’ve stayed with have pointed out how the money we’ve given them will help their whole extended family, such is the culture of sharing and friendship.

Economically challenged, it’s clear that liberty doesn’t fair much better for Cubans either, even if this isn’t that visible to us. There’s a distinct feeling of segregation between foreigners and locals in much of what you do: tourist-only buses (and indeed a bus company), hotels, beaches, restaurants, bars and cafes – some by law, and others due to the crazy prices charged for the western visitor. The Internet is off-limits to locals too – only those who need it for their jobs are allowed it at home, and access is extremely rare. Internet cafes are state-run and require a foreign passport to get in, and today’s wifi revolution hasn’t exactly hit yet – there are fewer than 15 wifi points (for foreigners only) in a country of 10 million! As a final marker of the level of communications, consider the national phone company van we passed on our way to the airport, advertising a great new way to get your phone bill – this fantastic technology called email! Yes, this is Cuba in 2012!

Then you have the question of the USA. Even today, Cuba is officially declared an Enemy Nation, and US Citizens face huge fines in the states for spending money in the country. It’s important to note that in spite of the two-sided war of words, the restriction is essentially one-way in practice: Cuba freely welcomes inhabitants from anywhere, including the US – it is the US government who place restrictions on their own citizens, although we still met plenty while we were travelling around. When you look at Cuba in its present day reality, it seems ridiculous and entirely farcical that the US sees it as a threat – what Cuba has is education, healthcare and culture, not an army or even a model of a truly functioning alternative economy to defeat the western system. Much like the situation in the occupied territories, it just seems to be a sad reflection of the US political system and indeed the votes in the swing state of Florida that Cuba is held in the same category as North Korea. I’m just waiting for Romney to declare it an addition to the Axis of Evil.

One piece of that puzzle is how Cuba has continued to function in spite of everything that’s been thrown at it. Right now, I can’t offer an explanation more sophisticated than “because of the people”; something I intend to read up on when I get back.

The other conundrum which is perhaps a bit more relevant for our trip is why Cuba has kept its political essence when the other states we visited with communist history essentially haven’t? After the chaos of Mao’s years, China is following a path of market reforms to its economy; Vietnam is decidedly capitalist in spite of the ‘Socialist’ in its official title; Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge saw utter destruction of a country through unspeakable horror. While Cuba remains a communist state, isolated, and with a decidedly non-market economy.

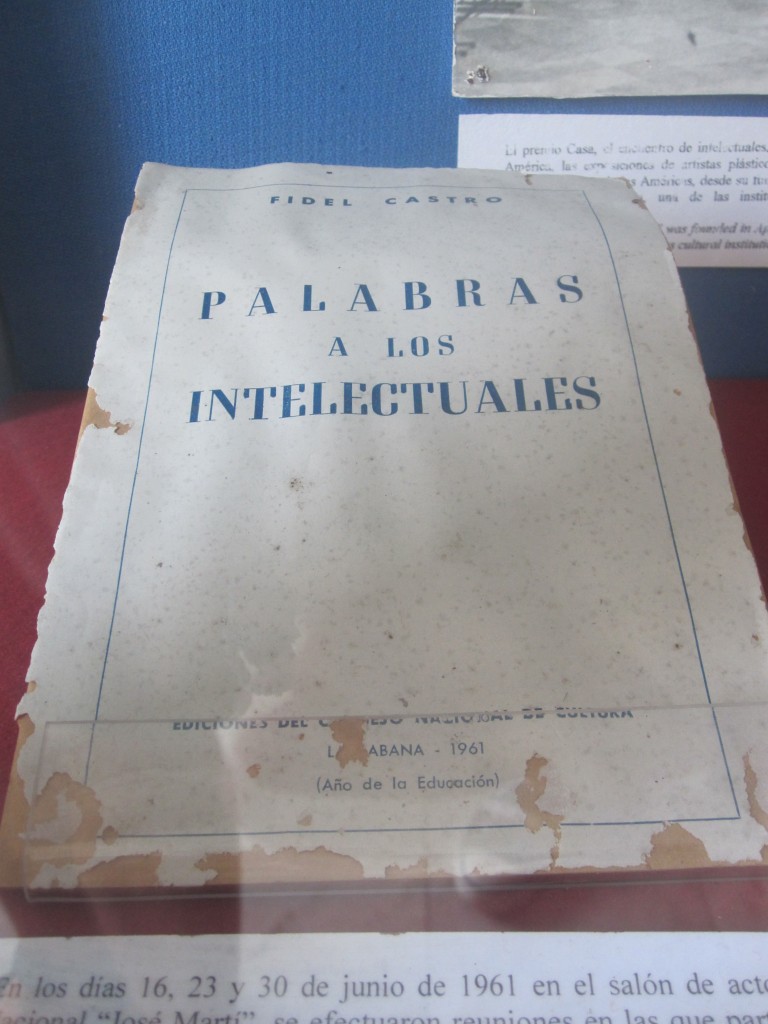

I think one answer is that this was an intellectual revolution that thrived – and still thrives – on education and literature, which have long since supplanted the gun. As we walked around the Museum of the Revolution in Havana, there was a pamphlet from Fidel, “Words of the Intellectuals”. There is definitely a case that at the point Mao and the Khmer Rouge were going into a frenzy decrying those who were educated as not true revolutionaries because they weren’t working class, Fidel and his bunch were promoting a civilised society, where learning is admired and not admonished. It hardly seems like a particularly wild move on their part, but the country now is a huge contrast to the horrors elsewhere.

Clearly that was then; right now, the lack of access to the Internet – probably the greatest learning tool ever – is an indicator of a very different present. I can’t help but think as we wonder around what we’re not seeing – what skeletons lie waiting to be discovered by a future government prepared to cast off the cloak of the past? As we’ve travelled, we’ve seen many examples of the horrors of repression from both sides of the political spectrum, and of course every eventual page of history is first written in the present.

It would be so wrong to leave the country on that note, because that’s not what defines the place we saw. In fact, it is those vibrant flourishes of life in spite of the system that make it what it is. Such warmth, energy, and passion – and that gorgeous feeling that as a traveller you’re not being welcomed with open arms because you look like a walking dollar sign, but rather because people are genuinely interested in finding out about your life and sharing theirs with you. And all this joy and colour dances there firmly in contrast to that soviet stereotype of drab concrete, dull monotony and a world of have-nots. Sure, the material possessions are refreshingly absent, but the ones that matter – human emotions – they’re here in abundance.

- Cars on the Malecón, Havana

- Buildings in disrepair

- More buildings on the Malecón – and some Iron artwork

- Couples gathered on the sea wall in the early evening

- Classic car

- Pink car and church

- You can see the Malecón stretching around the coastline

- Our posh night out

- Old Havana

- We had to do it once!

- The hotel used by the revolutionaries as their base for the first few years. The USA flag is back now though…

- Cuban flag

- A cannon looks over the city across the river

- I thought the Cuban missile crisis was long gone?

- Washing hanging to dry

- This is not staged.

- Words of the intellecuals

- Sane love is not love

- “Cretins’ Corner” in the Museum of the Revolution

- Final Mojito with our friends before flying out