Making our way into town on the back of a converted pickup truck after the journey from Hanoi, we could immediately tell we were going to love Laos. Vientiane is the capital city, but feels more like a sleepy village – the streets wonderfully quiet and absent of the chaos of motorbikes and honking horns we’ve come to accept elsewhere. There are pavements, giving it an air of sophistication, and no litter, which has plagued some of the places we’ve been. I could see Laura positively beaming as we passed various fountains on the way in to the centre – fountains which were actually filled with water and working, unlike most we’ve come across on our journey. The other immediately obvious thing are the temples, or wats, whose golden gleaming beauty and multi-headed serpents are unlike anything I’ve seen before. Being just over the border, I gather they’re quite Thai in style, very different to the Buddhist temples and stupas we saw in Tibet, even if their was some familiarity in seeing monks wandering around in their robes – now Guantanamo jumpsuit orange instead of the deep red of the Himalayan orders.

The speed dial here has been turned down to ‘laze’, echoing the Laos attitude that everything must have an element of fun to be worth doing, and reflecting the pace of life in a country that until the nineties apparently had no road connection to the world outside. Smiles are in abundance, and although certainly not naive about tourists (which are as common as those smiles), you don’t get the feeling people are after your money at every turn, which we’ve certainly had elsewhere. 60 kip (£5) for an en suite twin room at the Lao Youth Inn, an absolute bargain and our cheapest yet!

Escaping from the backpacker village that comprises some of the town centre, we went off seeking sights, and soon found ourselves with two very different snapshots of the national psyche.

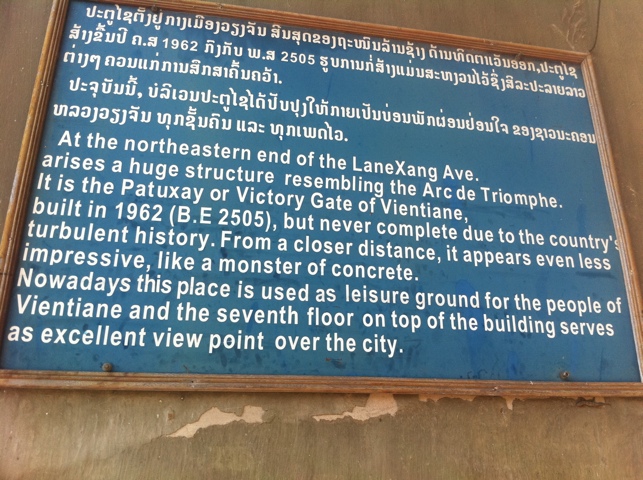

The Patuaxy, or ‘Arc de Triomphe’ sits in the middle of Vientiane’s central boulevard, a towering echo of the more famous Parisian monument. It’s huge, at seven stories high, and the views from the top formidable (once we’d passed through no less than four gift shops on the route). It’s also known as ‘The Vertical Runway’, as it was actually built using cement given by the American Aid programme in the sixties for the construction of a new runway at the airport! As we found out, Lao’s relationship with America became pretty loveless during this time, but this it was an interesting reminder of how aid can be diverted. The sign at the monument itself also has a touching imprint of Lao honesty and naivety about western notions of marketing. One hilarious sentence reads “From a closer distance, it appears even less impressive, like a monster of concrete”.

Our other snapshot of Laos life was decidedly more sombre, with a visit to the local NGO COPE, the Cooperative Orthotic and Prosthetic Enterprise, which works with those who have lost limbs. Going round their permanent exhibition, we learned about UXO, or UneXploded Ordinance – Lao has the grim title of being officially the most bombed country on the planet, with America’s ‘secret war’ in the country happening alongside the more public atrocities in Vietnam. A red dot in the picture below indicates each bombing sortie in a war that was being officially denied by the US – targeting the ‘Ho Chi Minh’ trail into Vietnam, as well as political targets in the ‘Plain of Jars’ in the north of the country. According to official US figures, 2,093,100 tons of ordinance were dropped over 580,944 sorties, equivalent to one B52 bomber every six minutes over the nine years of the war. Notwithstanding the civilian deaths from the campaign itself, 1/3 of the population became internal refugees, and the legacy of the cluster bombs dropped still kills one person in rural Laos daily. It’s believed that 30% of the submunitions didn’t go off, leaving millions of grenade-sized bombs scattered in the countryside. Tragically, in recent years the cost of scrap metal has risen, with many poverty-struck villagers and especially children now trying to make money harvesting the metal planted by war. Half of reported UXO accidents happen to those trying to salvage munitions. Despite the efforts of the UN and mine clearance organisations like MAG, at the present rate it will take another 200 years before Laos is clear of this horrific legacy from decades ago. And all this from a war that didn’t exist.

Our final day in the capital was Lao National Day. In other places this might have been the time for parades, street parties and celebrations. In Laos, it apparently means it’s an even sleepier day than normal! Fortunately for us, it meant we had some time to see some more of the town’s

Wats, and then wander in the brilliant afternoon sunshine down to the Mekong river, where we met some monks strolling along the sandy bank. We had a lovely chat with them, inquisitive about our lives back home and what temples we worship in. We explained the ‘Christian Temples’ attended by some on Sundays – the concept of many being non-religious is always a tricky one – and also a little about our trip around Asia, particularly Tibet. Both aged 21, they were keen to practice their English and we had a great time – even if we weren’t able to get much out of them about their lives and whether their calm smiles of the street extend within the monastery walls.

Simon

“According to official US figures, 2,093,100 tons of ordinance were dropped over 580,944 sorties, equivalent to one B52 bomber every six minutes over the nine years of the war.”

D:

That’s absurd.